BTS is a mirage.

BTS is a mirage.

This is something I’ve been thinking about as Tom Breihan moves closer and closer to “Dynamite” in his column The Number Ones. I wrote a response to his book chapter on “Dynamite” back when I read it in 2023 not because I have some obsession with The Number Ones (although I love the column) but because I think Breihan is a good bellwether for what the normie music enthusiast has learned about K-Pop and BTS since they popped up in the West as a bubblegum boy band in 2017.

Much of what can be “learned”—and I use the term very loosely—about BTS from mainstream sources is a combination of press releases regurgitated by hack journalists and fanon built up by fans of the group.

Here’s a prime example of the kind of bullshit coverage BTS receive as spun by one of the worst offenders of bullshit boy band coverage in mainstream media:

BTS has also been nominated for five Grammy Awards. Their first, for “Dynamite” in the best pop duo/group performance category, marked the first time a K-pop act received a Grammy nod.

As their global popularity grew, the septet also became international advocates for social justice.

So here we have Grammy-nominated (™) world class musicians BTS who are also major social justice advocates. I mean, they’re basically Wyld Stallyns but from Korea instead of San Dimas, California!

Except it’s all a mirage.

BTS is a product of BigHit Entertainment, founded in 2005 by Bang Si-Hyuk, son of Bang Guk-Yun, a high ranking government official at the Ministry of Labor. Bang Si-Hyuk came from a very wealthy and privileged background. He graduated university from the Department of Aesthetics and went to work as a songwriter and producer for JYP Entertainment in 1996 under Park Jin-Young. He worked with g.o.d. among other JYP acts and specialized in smooth ballads. Here’s one of his fondly remembered g.o.d. songs, “왜” (Why) :

In 2005, the K-Pop industry was in something of a slump. The first generation of K-Pop (as it’s been retroactively dubbed) had faded in popularity and Bang at this point left JYP in order to strike out on his own. As he explained in a 2018 interview [machine translation]:

Ultimately, I hoped to create a meaningful model for the industry. Until then, agencies were obsessed with promoting individual artists. A single singer or album failing meant survival. In this market with its extreme ups and downs, I wanted to create a company that could adhere to the rules and achieve sustainable growth.

So, the aesthetics graduate looked around at the K-Pop industry, decided that focusing on the artists and music alone wasn’t a solid plan for sustainable growth and decided that his first project with his new company BigHit Entertainment was going to be an ambitious multimedia webnovel called Syndrome.

I wrote about Syndrome in depth in the post linked here for the curious but the TL;DR is that it was meant to combine music, webnovels, webstoons, and parasocial relationships, into one overall package. The idea was that fans would read the webnovel—with art based on real actors—while listening to songs associated with the story. Fans were also then encouraged to ship the real life actors that the art was based on. You’ll see echoes of this idea throughout Bang’s career, especially in BTS’s HYYH-verse which is probably the most successful of Bang’s attempts to craft his ideal 360 degree fandom product.

While Syndrome was meant to be a stable base for company growth by avoiding over-reliance on a single artist or album, what ended up happening was that it was so completely rejected by fans as a cynical cash grab that it tanked the careers of everyone associated with it. Bang had been loaned a very promising young trainee from JYP Entertainment named G.Soul and the association with Syndrome and BigHit stalled his career completely. The author of the webnovel also had her career ruined.

Bang, in a pattern that would repeat itself throughout his career, shook off the major loss as no big deal, reached out to his many connections, and tried again. As he explains in the 2018 interview linked above, his friend Park Jin-Young encouraged him to stick with “Black music” and, with the help of the G-Funk loving producer PDogg, that is what Bang does with 8eight, who he intended to be something of a Korean Black Eyed Peas.

Here is 8eight with a 2008 song, “Let Me Go,” featuring Cho PD, one of the main characters of my popular Episode 50, which dives into the origins of the “hip hop idol.”

8eight did well enough but their (modest) success as pure artists wasn’t what Bang was after. In Bang’s telling, after 8eight proves he’s not a complete fuck-up, he’s approached by Park Jin-Young to take over management of an idol group, 2AM, the vocal-based ballad counterpart group to JYP Entertainment’s pop powerhouse idols 2PM.

Again, going back to the 2018 interview, he puts it like this (emphasis added):

Bringing 2AM on board was a wise decision. The market was shifting from "digital music"-focused singers to idol-centric ones. Big Hit Entertainment was also at a point where it needed to transition into a company that created idol groups.

It’s unclear when exactly Bang decided that BigHit Entertainment needed to transition from artists to idols but I’m guessing that it was about 2010 when he got a massive hit with idol group 2AM.

So, as 2AM was hammering home to Bang that he needed to get in on this idol group action, BigHit Entertainment had a pool of trainees that had been intended to form a YG Entertainment style hip hop group like 1TYM. The push to get hip hop trainees has to have been thanks to JYP’s advice to do “Black music” because Bang had not previously demonstrated any interest in—let alone any affinity for—hip hop or rap. His wheelhouse was, and is, MOR ballads.

In a 2015 interview with HipHopPlaya, the then-Rap Monster explains how he landed at BigHit Entertainment [machine translation; emphasis added]:

But then, when I was just going to study, I got a call from Sleepy from Untouchable, and that led me to audition for this company. At first, Bangtan wasn't in this format. It was a non-dancing format, similar to YG's 1TYM. That's why I joined this group. They said such a big company would let me rap, the way I wanted to. Also, I had just failed an audition for Big Deal Records, so I was desperate. I thought I absolutely had to do this. It was the perfect company to realize my dream of proving my worth to more people. But when the group format changed to idol, I was confused and despaired. But then I accepted it again... and that's how I got here.

PDogg adds this context from a 2013 interview [machine translation; emphasis added]:

Cha Woo-jin: How did the Bangtan project come together?

PDogg: Around 2010, I was drinking with Sleepy, and he said there was a kid we were close with, 17 or so, a high school freshman who sang incredibly well. He asked if we wanted to listen. So I listened, and I was like, "Oh, he's dope." So I told Si-hyuk about this kid, and he just clicked with me. That's how the project began.

Cha Woo-jin: What was the reason for that plan? Because you wanted to do hip-hop yourself?

Pdogg: No. It was more like, "We can't bury these talented kids." Rap Monster's friends were all born in 1994 or 1995. But they were really good. I thought, "Wow, there are kids this talented," and then I noticed they were friends with Block B's Zico. That's what it was. Seeing that there were quite a few of these kids, I told Si-hyuk about it. At first, we called it the Bangtan Crew. Then, as the direction gradually shifted to idols, we reorganized the group. As dance and performance became more involved, we reorganized the kids who were struggling. That's how it went.

BTS fans have retroactively canonized Rap Monster as a giant of the underground rap scene but the truth is available if you dig deep into the archives. He was a hanger on of the scene and active online on the same hip hop message boards as Zico. And Zico, who would debut with the hugely popular Block B in 2011, was actually a very buzzworthy young talent who had joined up with Cho PD’s new label. Infamously, Zico once referenced the young Rap Monster in an online rap battle with a “hater” by saying that his opponent was so lame that he even got his ass handed to him by Rap Monster.

Reading between the lines, what it looks like is Sleepy told PDogg that Zico had a friend who was available and PDogg thought it would be a good idea to have his own Zico and brought the idea to Bang who okayed it.

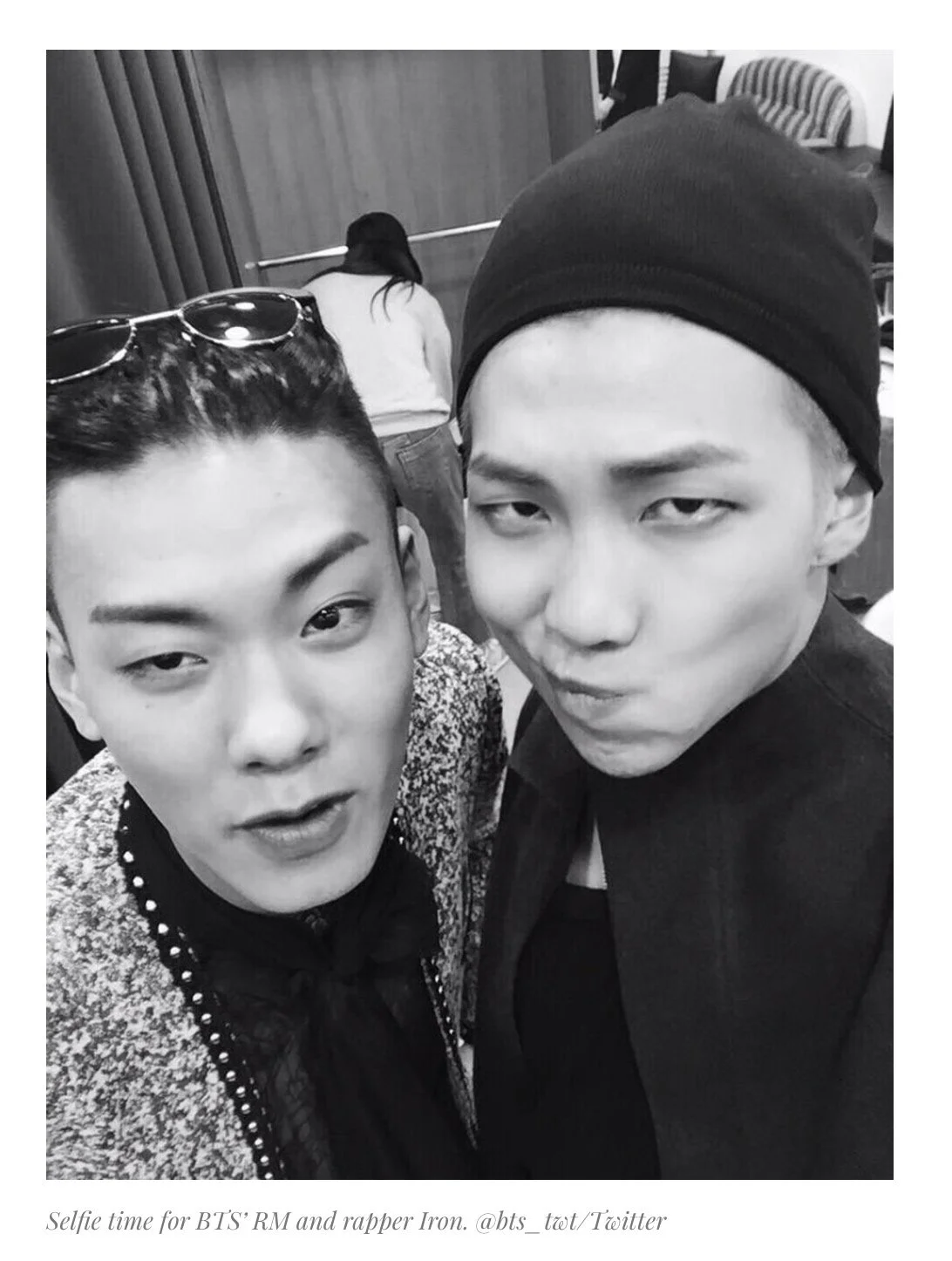

Rap Monster then brought his “crew” to BigHit with him and the original Bangtan line-up was Rap Monster and his good friends Iron and Supreme Boi. When Bang changed format for the group from 1TYM to dancing idols, Iron and Supreme Boi left. Rap Monster, who as he said above, had been desperate for any company to accept him, stayed behind.

Iron you may remember from news coverage for coming runner up to Bobby in season 3 of the rap competition show Show Me the Money and then from being arrested for drugs (2016), beating his girlfriend to a bloody pulp (2018), beating his roommate to a bloody pulp (2020), and then finally killing himself in 2021.

Supreme Boi you may know from the credits to all of the best, early BTS songs. There is very compelling evidence that Supreme Boi is, in fact, the actual songwriter and producer behind most of Rap Monster’s early work with Bangtan. In 2016, Supreme Boi went on walkabout and let it all out:

So, after the real rappers in the original line-up peaced out, Bangtan was reformed with Rap Monster and some odds and ends of trainees kicking around BigHit. The rap line that reformed now included Suga, an unremarkable rapper who—like Rap Monster—was desperate for anything, and J-Hope, who was not a rapper at all but who had previously trained at BigBang Seungri’s dance school so maybe the association with BigBang was good enough for BigHit.

But it wasn’t this newly formed Bangtan project that was the first idol group from BigHit but a girl group called GLAM that was a joint project with Source Music, a company run by a buddy of Bang’s from JYP Entertainment. (Source Music would later be wholly acquired by Bang’s conglomerate, Hybe.) BigHit handled the production for GLAM and the lack of a musical or artistic identity that will characterize all later BigHit and then Hybe artists is fully evident with GLAM. Production for the group cribbed bits and pieces from acts like f(x) and 2NE1 and the end product was cute but ultimately forgettable.

GLAM would end up imploding spectacularly with one member getting booted for being a Super Junior sasaeng and then another going to jail for blackmail. It ended up being a silver lining for Bang and BigHit that GLAM had been so forgettable because they’ve now been successfully wiped from K-Pop memory and BTS hagiography just skips right by one of the reasons BigHit—a company founded by a political nepo baby with deep industry connections and who’d had a lot of helping hands—was struggling when BTS was in their early days: the GLAM fiasco.

If GLAM demonstrated that the aesthetics department graduate had a tin ear and no original ideas for idol pop, then the Bangtan project would solidify that. From the beginning the group pulled bits and pieces from other and more successful acts. The debut hip hop era was heavily influenced by BigBang, BAP (who were so popular at the time that One Direction infamously referenced them in a music video), and the aforementioned Block B.

Sonically, this early era leans heavily on PDogg’s love of G-Funk with Supreme Boi adding his more cheekily playful rap sound as they get into 2014-2015.

BTS, at this point, was a completely average mid-tier boy group. The example I like to use to demonstrate this is UNIQ releasing EOEO and then BTS releasing the extremely similar sounding DOPE within a few days of each other:

Not like any other groups, hmm…

But being a completely serviceable mid-tier boy group wasn’t good enough.

From the beginning of the group there had been an attempt to massage the narrative around them to one of both exceptionalism and authenticity. To that end, BTS did things like film a reality show of them connecting to “real” hip-hop in Los Angeles in 2014 perhaps with the idea that being shown adjacent to Black artists would transfer their cred to BTS via some sort of magical osmosis. (Did it work? You be the judge.) And infamously—but totally wiped from the record in English—Rap Monster and Suga attempted to mix with actual underground Korean rappers after they debuted in 2013 and were totally demolished by rapper B-Free who called them out both for plagiarism and for being fakes.

It’s important to note that they never try this again with Korean rappers. While other idol rappers would go on Show Me the Money (notably iKon’s Bobby who won over Rap Monster’s friend Iron in 2014, and Winner’s Mino, who came in second place in 2015), or appear on the show as mentors and judges, no member of BTS that debuted in BTS has ever tried their skills against other rappers.

I translated an interview with Saito Eisuke, who handled their Japanese promotions and two important points of the BTS media strategy in Japan he mentions are 1) deliberately targeting non-Kpop media who won’t know what they’re seeing is a perfectly average mid-tier boy group doing concepts yanked from other, more popular groups and 2) crafting a faux-organic growth narrative. Both of these strategies but especially the first one, would also be used to great effect in the American market.

So, in 2015, GLAM has fallen apart and BTS is stuck in the mid-tier with nothing to separate them from a group like UNIQ, let alone to reach the heights of a Block B or BAP. Bang gambles again on the 360 degree fandom product by rehashing Syndrome with what fans refer to as HYYH (Hwa Yong Yeon Hwa) or The Most Beautiful Moment in Life. Injected into the mid-tier boy group was a storyline about True Friendship (™), struggle, and homoerotic tension, that was meant to launch a thousand fanfics and fan theories.

It worked.

In fact, it worked so well that new fans to this day will get information on the BTS members that is drawn from their characters in the HYYH-verse rather than real life.

And this is not to dismiss HYYH, which is genuinely enjoyable and probably my favorite era of BTS—if you’ve never looked into BTS but are curious, HYYH parts 1 and 2 are the albums I’d recommend—but just to note that the storyline was a deliberate marketing strategy. As was the decision to boost HYYH in the album charts, a decision that worked in that it resulted in getting BTS’s name out there but also resulted in a blackmail trial where the very non-organic methods of boosting BTS were eventually put out in the public record...at least in Korean. It was a bold move to try and boost BTS in 2015, the year that BigBang released MADE and essentially dominated the popular music charts that year thanks to songs like “Bang Bang Bang.”

As we get into 2016, BTS is touring relentlessly and Supreme Boi, who had been responsible for a lot of their hip-hop content, takes a step back to work on his own material. The chameleon group is then given a concept following what the then-extremely popular group VIXX was doing. VIXX, who at the time were so popular that they were once kidnapped by the president of Kazakhstan’s daughter, had crafted an artsy multipart series using literary and mythological references. “Fantasy”, for example, takes listeners through the story of Hades and Persephone.

And just like that we see BTS abruptly switch gears from Block B knock-offs to VIXX knock-offs with “Blood, Sweat, and Tears”.

This is where things take an interesting turn. Up to this point, BTS had been received by K-Pop fans as nothing more or less than what they are: a middle of the road, not particularly original, third generation K-Pop boy group with annoying fans.

But if you remember Saito Eisuke’s stroke of genius to market the group in Japan not to K-Pop fans, that is exactly what happened in America: Non-K-Pop fans found BTS and were told they were exceptional. Some of these fans were migrating Directioners and began using their fandom’s practices in support of BTS in America. A few years ago, I spoke with an ex-BTS fans who was active in that time and she confirmed the fandom practice overlap, such as calling radio stations to request songs. As Monia, my favorite ex-Directioner, discovered, calling a radio station does nothing if they haven’t been served the song or DJs have been told not to play it. Despite the lore that has been built up by the BTS fandom it’s really important to flag here that fan power does nothing on its own. And, indeed, nothing happened with BTS until the American music industry started taking notice of this new influx of fans.

What ends up happening is following this new fandom influx, BTS fans take the Top Social Artist award from Justin Bieber fans in 2017.

It’s a life-line for Bang and his BigHit Entertainment, which had been floundering, and he makes the most of this opportunity. What appears to happen is that BigHit sees the influx of English language fans driven by fan networks on sites like Tumblr and moves to target them. There’s an infamous fandom survey released in 2017 that asked fans about their mental health among other things. This survey has since been buried and evidence erased but looking at mental health of fandom would seem to point to Bang and BigHit being aware of the kinds of things Harry Styles’ team was doing.

This is where I begin documenting what followed over the years as BTS was yanked from the K-Pop sphere and inserted into American/Anglosphere fandom spaces. This involves BigHit crafting a faux-narrative of “social justice,” which was dutifully parroted by the boy band hack I linked above, by retconning some of BTS’s earlier songs to fit the narrative expected by fans migrating in from Directioner spaces on Tumblr. And the faux-narrative of exceptionalism, which was dutifully parroted by Tammy Kim in her infamous New Yorker article.

Using the massive influx of money brought in by BTS fans, BigHit Entertainment was eventually restructured and taken public and renamed Hybe—the IPO launch is something Bang is under investigation for right now—and Hybe has spent the last few years gobbling up mid-tier companies and hollowing out the K-Pop industry in the manner of a vulture capital firm. BTS fans, after going scorched earth on producers, songwriters, rappers, journalists, critics, K-Pop fans, and BTS fans who get out of line, have found their powers depleted and the ranks of ex-Armys with receipts are starting to speak out.

I don’t know what the future will hold for BTS but I do know that the K-Pop industry is much worse off after their reign of mediocrity. I said in 2018 that the weight of expectations would crush the group and I think I’ve been proven correct. What had been a perfectly fine mid-tier K-Pop group was sold to the world as not only the jewels of Korea but the best and most original band since the Beatles. It wasn’t true and the group looks worse being held against the acts they ripped their concepts from then if they’d simply been allowed to stay a perfectly fine mid-tier group.

BTS is a mirage.