Sell out! With me oh yeah!

'Cause you're gonna go to the record store

You're gonna give 'em all your money

Radio plays what they want you to hear

Tell me it's cool, I just don't believe it

“Sell Out” by Reel Big Fish (1996)

After listening to a fantastic interview with music writer Dan Ozzi on Money 4 Nothing I picked up his 2021 book SELLOUT: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994-2007). The 1990s-2000s battle among music fans over “selling out” is one I was pretty familiar with, having come of age as a music fan through that very era but it’s been fun (and sometimes sad) reliving those years through the story that Dan tells.

To “sell out” to a major label meant not just abandoning pure punk ethics for corporate payola (see also: 2001 film Josie and the Pussycats, which I wrote about here) but a change in sound as well as a change in the makeup of the audience, and it wasn’t always positive for the fans who had been there from the early days. There were real growing pains.

I’m outing myself as a massive dork with this but I loved Ben Folds Five debut album Ben Folds Five (1995), which was packed full of uptempo, energetic, irreverant piano-driven pop punk but after they got signed to a major label and had a hit with the extremely emo “Brick”--a song I loathed then and continue to find unlistenable--the entire sound and dynamic of the band changed. Their major label debut still had some of the fire of Ben Folds Five with songs like “Song for the Dumped” but it wasn’t quite the same. Sure, I could groove to a more mellow song like “Battle of Who Could Care Less” (the opening lines of which take me right back to 1997) but the hordes of new fans drawn by the emo stylings of “Brick” were not the same fans who had pogoed around to “Underground," a song that opens with the line: “I was never cool in school.” The locals and normies pulled in by “Brick” had been cool in school or at least weren’t the same dorky music press reading nerds who had glommed onto the debut album. I tried to make myself like this new sound but just couldn’t.

The band broke up shortly afterwards. (Although I will add that the reunion album from 2012 more or less returned to the sound I’d enjoyed as a dorky teen and was quite enjoyable.)

Was I just being a punk snob for abandoning Ben Folds Five after their major label jump? I don’t think so. I was reacting as a fan to real changes in the product.

And it’s not just the music. Things like venue size for live shows--going from paying reasonable ticket prices and being able to bullshit with the band at the merch table to paying through the nose for an impersonal arena seat. I experienced all of this from the fan’s side but what Dan Ozzi does is capture the angst experienced by the bands at the same changes. Take At the Drive In, for example, who loathed the aggressive bros they began seeing at their intense stage shows after jumping to a major label. (Please read about Jessica Michalik who was killed by a crowd crush at Big Day Out in 2001 during a performance by Limp Bizkit. At the Drive-In had earlier in the festival stormed off stage without finishing their set because they’d been concerned over the audience’s safety.)

What loyalty do we owe to a band as fans when our relationship goes from something personal (i.e. chatting at the merch table) to something impersonal (i.e. getting email blasts from Sony Music reminding you to buy, buy, buy!).

I know I always go back to the Black Keys interview on Joe Rogan but weighing the costs and benefits to selling out is complicated.

At the end of the day, if the music stays good--for me, anyway--I’ll remain a fan.

This idea of “selling out” is something that has mostly vanished from popular discourse, although the roots are still there, especially among the generations that came up during the era discussed in Ozzi’s book. You see these ghosts of a cultural argument from two decades ago still haunting American-centric K-pop stans. (Possibly because many of the loudest voices dominating the conversation are also from the same era.)

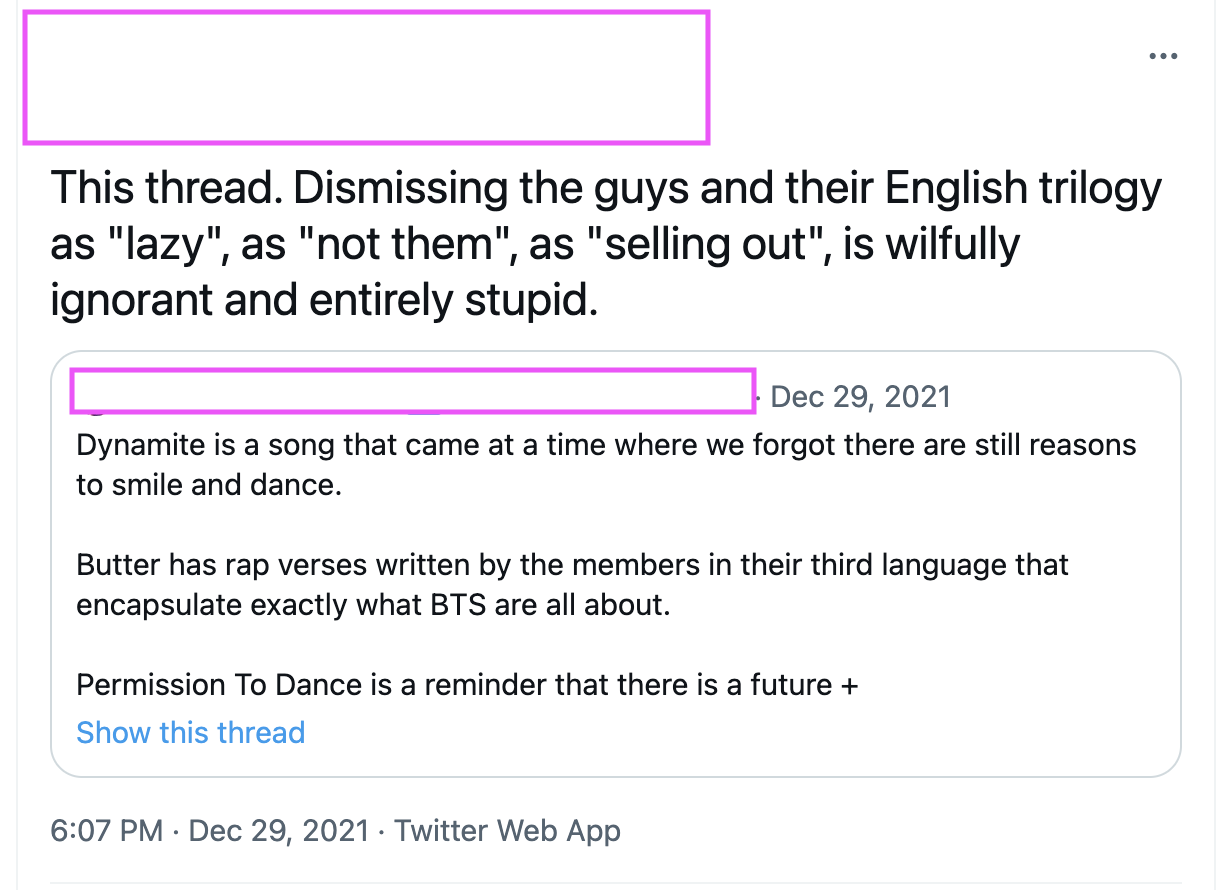

BTS, in particular, has come under fire for “selling out” by releasing three English language songs after RM said they would never do such a thing: “[W]e don't want to change our identity or our genuineness to get the number one. Like if we sing suddenly in full English, and change all these other things, then that's not BTS.”

Whoops. That’s certainly hypocritical—especially when BTS’s fans had used this as a hammer against other groups who had done English songs before BTS did—but is that selling out? There are definitely shades of Jawbreaker insisting they would never jump to a major label only to do so when they needed the money but BTS was never “independent” in the way that Jawbreaker were. Not musically or financially. They never had full control of their image or music to begin with.

What has been internalized among K-pop stans as “selling out” is less about artistic purity and more about questions of scalability. Can a formerly small group preserve their relationships with and among the fans? Can the group successfully bring their fans along when there are changes in the sound of the group?

SHINee’s Taemin has spoken about being unsure of the reception of “View” because it was such a departure from what had come before. When the previously small scale and ballady Winner returned after a long hiatus, they took a huge gamble with tropical house-flavored banger “Really Really”. When BigBang dropped a song after a five year hiatus, they didn’t go for a hooky banger (their trademark) but a sentimental ballad. All of these songs were very well received by fans and the public alike.

The difference with BTS and these other groups is that BTS were far closer to what I experienced with Ben Folds Five a couple of decades ago. They had had an almost complete turnover in the fandom leading up to and during the release of the bland and middling “English Trilogy.” Older fans were crowded out by these new recruits and were left wondering who was this kindergarten colored boy band and what happened to the irreverent idol group that had sung “War of Hormone”.

But even when a change in scale of popularity is navigated successfully there can and will still be fans who lament the loss of “their” group. Green Day is the example of this in Ozzi’s book but in idol world I think it has to be Arashi. Right around their tenth anniversary in 2009, Arashi experienced a rapid boom in popularity which correlated to a massive surge of new fans, a change in the quality of the music being produced, and a new visibility of the group with the general public. Fans who had fallen in love with the dumb guys making boobie jokes on late night television didn’t quite know how to handle the new, more polished image. Concert tickets surged in price and became harder and harder to get. And their music now had a real budget behind it and no longer had the ramshackle homey sound of previous releases.

Some fans complained about everything sounding too “digital” or “autotuned” than what they were used to. In truth, they were hearing a change in the sound and style of what Arashi was doing. You started seeing a bigger mix of names (including some European names) in the song credits as they were able to branch out a bit more in their song selections. And the quality of the recordings improved dramatically. As a pop fan, I think those post-boom albums are some of the finest idol pop ever but if you were emotionally attached to the earlier stuff… well, I can see how it would be disappointing.

Did Arashi “sell out”? No, they just became a lot more popular and with that increased visibility comes tradeoffs. Good-bye boobie jokes and hello serious visits to disaster sites.

Did BTS “sell out”? No, but they did make changes to their sound and content that a lot of their long time fans did not enjoy.

Selling out may not be in the discourse much these days but I think there’s still a lot of (deserved) angst around the changes that come when a group tries to level up their popularity. Maybe we need a new phrase to describe it. “Popularity kills”?